Guest post by Douja Darej

Sometimes the most obvious questions are the hardest to answer. And this is something all physicists and scientists in general get to know very early in their career. Particle physicists are confronted with very raw truths that usually seem too obvious from afar, when in reality a good question can only lead to another. On many levels, high energy physics is a particular field: Huge experiments, counter intuitive aspects of how the quantum world behaves, patterns of nature that can only be described by models, estimations, hypotheses, simulations… One of the things that led me to follow particle physics is how curious I always was about the way we would see this world if we knew how it really worked, only to find out that the more I dived into science, the more confused I got. So I decided to ask some of my colleagues in the CMS experiment (Compact Muon Solenoid at CERN) from different institutes around the globe how they felt about this.

The CMS experiment is one of the biggest scientific collaborations in the world, gathering more than five thousand active people, from physicists, PhD students, fellows, to engineers and technical staff… working on one of the biggest detectors ever built by humans. An incredible machine that, thanks to the great efforts put together for years, captures pictures of our reality we are not very used to seeing. Pictures that are quite strange, where space and time get to work differently, where the numbers start to become hard to imagine, where equations are the common language and algorithms become the biggest weapon to fight the huge amount of information coming from particle collisions. Installed in one of the four collision points of the 27 kilometre circumference tunnel of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the 14 ton machine uses the most advanced and precise technologies to witness some tiny forbidden phenomena that can only happen in this context on earth, reminding us about the very early moments of the Universe after the big bang, and the very far away spots of our galaxies we usually tend to forget about.

In this factory of something close to magic but also representing the texture of the reality we’re living in, particle physicists analyse the data, and compare it to the theories that aim to explain how matter and energy behave in the smallest accessible scale and the highest energy available. In this challenging psychological environment, particle physicists have to continuously adapt their perception to find the perfect balance between being good scientists who see things from a neutral and objective point of view, and human beings constantly confronted to how little they know about themselves and about this world.

So how hard is it to find the balance between a stunning fascination and never-ending confusion? I asked my colleagues 3 questions : What do they do for CMS? How does learning about the infinitely small impact them? And what still impresses them everyday in their jobs?

Some common aspects came back in the different answers of these inspiring minds. The most important of them being the continuous excitement about infinite learning and mastering a science that we decided to devote our lives to. It is not easy being a particle physicist, especially when it comes to realising how tiny we know compared to what we don’t. But there is a small gap between our excess of curiosity and our limitations where we seem to find the space for our minds to expand enough to connect to this deep concreteness that feels familiar and yet very mysterious.

As Michio Kaku said : “Physicists are made of atoms. A physicist is an attempt by an atom to understand itself.”. This quest for answers is even more interesting when the questions you ask yourself are so fundamental that they concern everything you touch, see and feel. Our reality is for sure shaped by our senses and intuition, but also by the information we take the time to assimilate. As explorers of the subatomic world, this hard science tends to easily blend to a philosophical and metaphysical dimension where objectivity and intuition are usually not enough to ease the confusion. But knowing we are thousands working towards the same goal is quite comforting.

The communication of the information on such a large scale with a precision that is big enough for excluding any risk of dysfunction, the necessity for continuous alignment between the different specialities and the absolute need to control the tools and machines we build are some of the tasks that are necessary in this domain. But some important soft skills are also required: training our minds to have the needed flexibility to adapt to this maze of the unknown, finding the serenity to be patient, motivated, rigorous and precise are other kinds of challenging traits of character that particle physicists need to work on all along their careers.

Don Lincoln: (Physicist, Fermi National Accelerator Lab. (Fermilab)

Don Lincoln: (Physicist, Fermi National Accelerator Lab. (Fermilab)

I do a few things for CMS. I am working on the high-granularity calorimeter (HGCAL) upgrade. I am the international Q&A manager and work at Fermilab to build the scintillator part of HGCAL.

I think I’ve always known that the world can be understood to a large degree by looking at smaller and smaller building blocks. It’s not super different from being a baker, where if one understands the ingredients and how they react to heat, one can make a better confection. For the Universe, all information is encoded in the building blocks and the rules that govern them. This mindset perhaps leads one to a practical place, where one sheds mystical thoughts and tries to understand the stern reality imposed by the Universe. It also is important to understand that it is very easy to fool oneself when we look at the data. One of the most important skills of a scientist is to look at the data and ask if we’re being fooled and how we can make sure that our conclusions are robust.

The thing that amazes me every day is that I get paid to study the deepest mysteries of the Universe. I am gratified that society agrees with me that it is worth supporting scientists to ask and attempt to understand the rules that govern the matter and energy of the Universe.

Caroline Collard: (Physicist, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

Caroline Collard: (Physicist, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

I am analysing the data to find signals coming from new unknown particles. In parallel, I am also setting up a small detector to identify precisely where the Cyrcé beam is passing, which is important in tests of modules for the High Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC) CMS detector.

In some sense, learning about the infinitely small contributed (and it is still happening!) to feed my curiosity about how things work.

However, I am not the kind of person who sets down a computer or a toaster to see inside. I find it amazing that humans are able to express the laws of nature, of physics. Searching to increase the knowledge of Humanity, to better understand the Universe in which we are leaving, is really something special to humans…

I really like the fact that my work offers me a large variety of possible tasks. I can change activities and continue to discover new things to do, to try, to learn.

Juliette Alimena: (Fellow, CERN)

Juliette Alimena: (Fellow, CERN)

As a CERN fellow, most of my time is spent searching for new phenomena and analysing the data. I have also contributed to collecting the data and operating the detector, reconstructing particles from the raw data, and designing upgrades of the detector for the future.

My training as a scientist has a major impact on how I see the world. As scientists, we are trained to question what we think we know. "Is that really the way that works? Is that what the evidence leads us to believe?" are constant questions in our minds. Thus, we keep a healthy amount of skepticism about the beliefs of others, but even more importantly, we keep questioning our own beliefs. This is not to say that when the evidence points to a conclusion, we should continue to worry it's not right. Rather, we remain open to changing our minds. I think "I don't know" is one of the most powerful phrases in the English language because it can inspire us to find the answers, and it gives us the freedom to question the status quo.

The thing in my job that amazes me every day is the intelligence, hard work, and perseverance of my colleagues. As a member of a collaboration of about 4,000 scientists, I am inspired daily by their quest to find the truth about our Universe, on a microscopic scale.

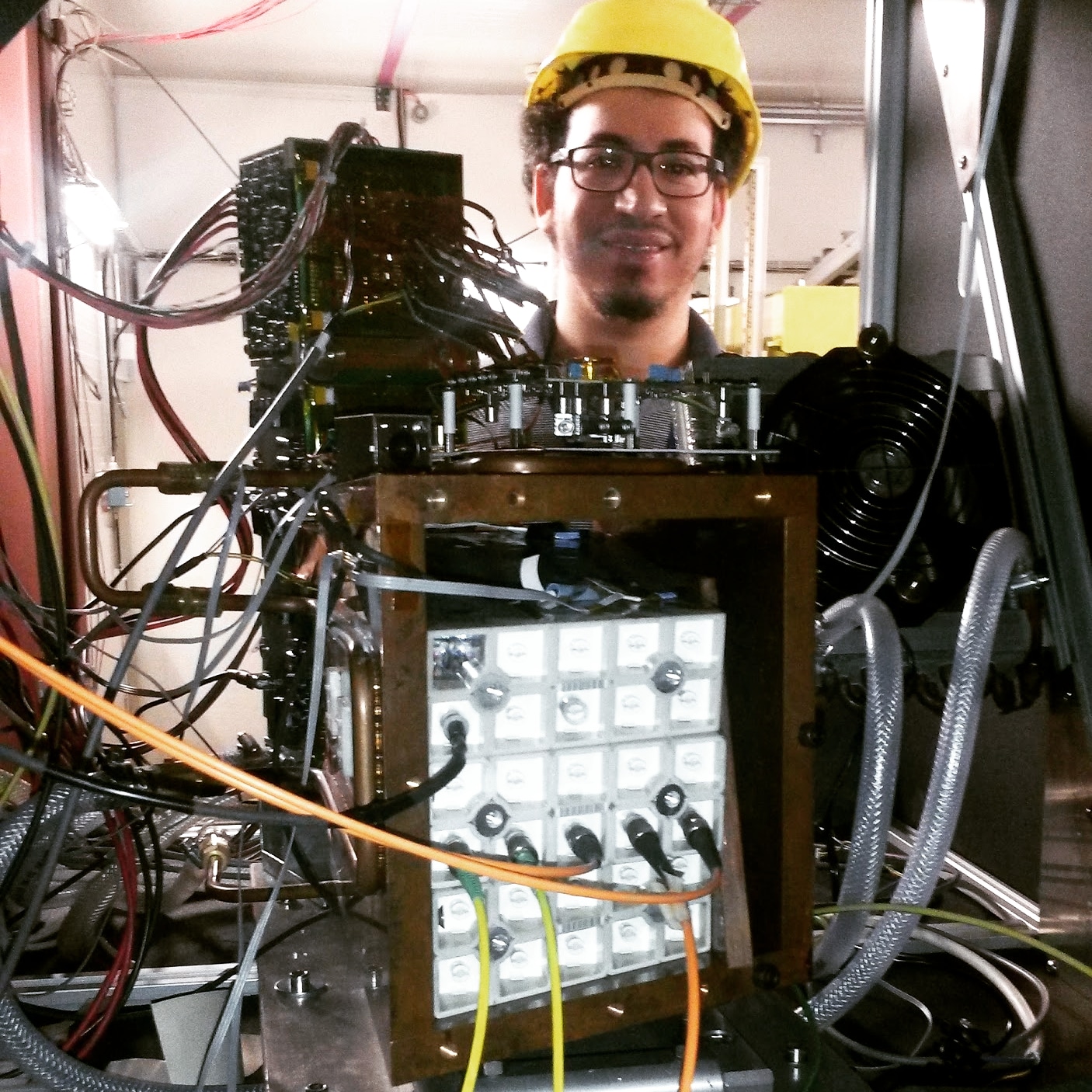

Younes Otarid: (PhD Student, Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY))

I am working on Data Acquisition and Test Systems for the Phase 2 Upgrade of the CMS Outer Tracker, as well as a search for super-symmetrical top squark pair production in a final state with two tau leptons in proton-proton collisions using CMS data.

I feel like getting to work on the infinitely small lets the realm of one’s reality oscillate between a dizzying level of abstraction and an assault of concreteness. The world ends up building up to theoretical predictions and experimental evidence, if not to metaphysical questioning when one is also interested in the philosophical aspect of it. So yes, embracing the world as a seeker of the unknown, be it infinitely small, is a very special and exciting journey for whom truly dives into it. It is an open door on constantly expanding horizons, offering a unique experience of a universe still to be understood.

What fascinates me the most about my job is the tremendous collaborative effort set in exploring theoretical endeavours and building complex machines, all lined up to one and only ambition: unveiling the mysteries of the Universe.

Pieter David: (Physicist,. Universite Catholique de Louvain (UCL))

Pieter David: (Physicist,. Universite Catholique de Louvain (UCL))

I work on the calibration and hit reconstruction software for the strip tracker, data analysis, mainly a measurement of the cross-section of the ttW process, and the development of software used for analysis in my institute.

Very often when people look at the night sky they say that it makes them feel small in comparison to the universe. I have something similar with studying the infinitely small: the subatomic scale is far away from what surrounds us in daily life, but ultimately we, everything around us, and the Universe (or at least the part we understand) are all made up of the same elementary particles - I find that very humbling.

Another, more prosaic, consequence of spending time with physics and mathematics is being aware that numbers and equations may seem abstract, but when they describe phenomena around us, differences that may seem small can have huge consequences (e.g. in the spreading of an epidemic, or global warming).

Studying collisions at these high energies is a massive undertaking, so we are doing it as part of a large collaboration, working together on a day-to-day basis with people in very different places. While not always easy, it somehow ends up working out - that continues to amaze me.

Eric Chabert: (Physicist, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

Eric Chabert: (Physicist, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

My activities on the detector are devoted to performance measurements and simulation of the current silicon strip tracker as well as the construction of the future one designed for the high luminosity phase. After being involved in top quark physics, I focused my research on supersymmetry, searching the top squark with the motivation of finding a solution for the hierarchy problem. Nowadays I investigate the hypothesis of supersymmetric particles having a lifetime long enough to appear as a slow and very ionising particle.

Behaviour of the matter at the smallest scale has an attractive power on a large audience and was at the origin of my career. I am still fascinated by the idea that observable phenomena at a macroscopic scale could be driven by the "quantum world" (spin effect, loop effect …).

Particle physics, despite its technical complexifications and its need for scientific specification, is deeply connected to philosophy in its foundations and the quest that is pursued.

Teaching, giving seminars, participating in outreach actions are oxygen breaths to remind us of the origin of our motivation and to share it with the general public.

Beyond the beauty of the ideas that we have used to describe the world, I am also stunned by the scientists' creativity that allows our community to assess the behaviour of matter at the smallest scale from indirect observations. While nobody has ever seen, caught or handled a particle strictly speaking, we have been able to measure their properties such as their mass or lifetime.

Beyond those deep thoughts which are the essence of our domain, everyday's activities are devoted to more practical questions in domains as various as data analysis, statistics, software, electronics, mechanics… What keeps me deeply attracted to my job is the continuous process of thinking that we apply in a variety of domains: finding explicit formulations of the problematics, drawing hypotheses, searching for answers, making interpretations… As experimentalists in a large world-wide collaboration, we have the chance to interact on a daily basis with engaged researchers, engineers, students… Brainstorming sessions where the outcomes would only result from collective intelligence are probably among my best professional memories.

Yuri Gershtein: (Physicist, Rutgers State Univ. of New Jersey)

Yuri Gershtein: (Physicist, Rutgers State Univ. of New Jersey)

Right now I'm looking for new physics (long-lived particles or anomalies in high pT jets) in Run 2 data and work on HL-LHC Outer Tracker construction and its use in the L1 trigger.

Not sure if it was the study of the infinitely small that had an impact on me, probably just physics itself. I think appreciating how small the human perception range is compared to what's available in the Universe is very humbling. On the other hand it makes me appreciate the fragility of the human condition in the indifferent universe more.

What fascinates me every day in my job is that I'm still able to do it and get paid for it? Little more seriously though, the diversity of problems and daily tasks that I need to do is amazing.

The relative freedom to choose which task to focus on at the moment is why this job feels fresh to me even after so many years of doing it. The way our huge collaboration works, despite the multitude of personal and organisational conflicts of interest has been a source of fascination and amazement to me over the years.

Mario Sessini : (PhD student, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

Mario Sessini : (PhD student, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

As a PhD student from the Strasbourg CMS team, I am analysing the data collected by the CMS detector for the purpose of studying the properties of the Higgs boson.

Learning about the infinitely small is a difficult yet fascinating journey during which your everyday intuition has to be put aside. I believe that through the understanding of infinitely brief events shaping so long ago a universe in which we can exist today, particle physics has deeply affected my personal relationship to time. It is hard to tell how fundamental research can assist you in your daily life, but it sure gave me a new way of thinking and a wider vision of the surrounding world.

As a CMS member, I truly feel lucky and amazed every day by the thought of working with people all together at the front line of human knowledge in a one of a kind experiment.

Barbara Alvarez: (Physicist, Universidad de Oviedo)

I am Barbara Alvarez from the University of Oviedo. In the CMS experiment I work in the Muon detector group as part of the Drift Tube team, in particular in the longevity activities, and I also work in physics analyses mainly in Standard Model, top and Higgs groups.

I don't think I am different from knowing about the tiny building blocks of matter, but it is a privilege to work in such an atmosphere, with such great people. I love to be part of the high energy physics community involved in understanding the origin of the Universe and beyond.

Learning about the smallest scale makes me realise how infinitive the Universe we live in is.

I am amazed by the people that had such brilliant ideas to build a machine like the CERN Large Hadron Collider and precedent machines made to look at the most fundamental particles in nature.

Badder Marzocchi: (Post-Doc, Northeastern University)

I am a post-doc physics researcher. My research activity is focused mainly on 3 topics: calibration of the electromagnetic calorimeter of CMS (ECAL), R&D studies for CMS detector upgrades devoted to precise timing measurements, and data analysis searching for exotic diphoton final states.

After knowing that the cosmic scales are reached through infinitely small particles, I realised how tiny is human kind, and how eager human actions are compared to the cosmic events. Thanks to this, I started to value a little bit more the things in normal life and care much more about nature and environment, knowing that also small actions matter.

What still amazes me every day is waking up every morning knowing that, if I sharpen my wits, I can find new ways and new techniques to develop my research and improve it step by step.

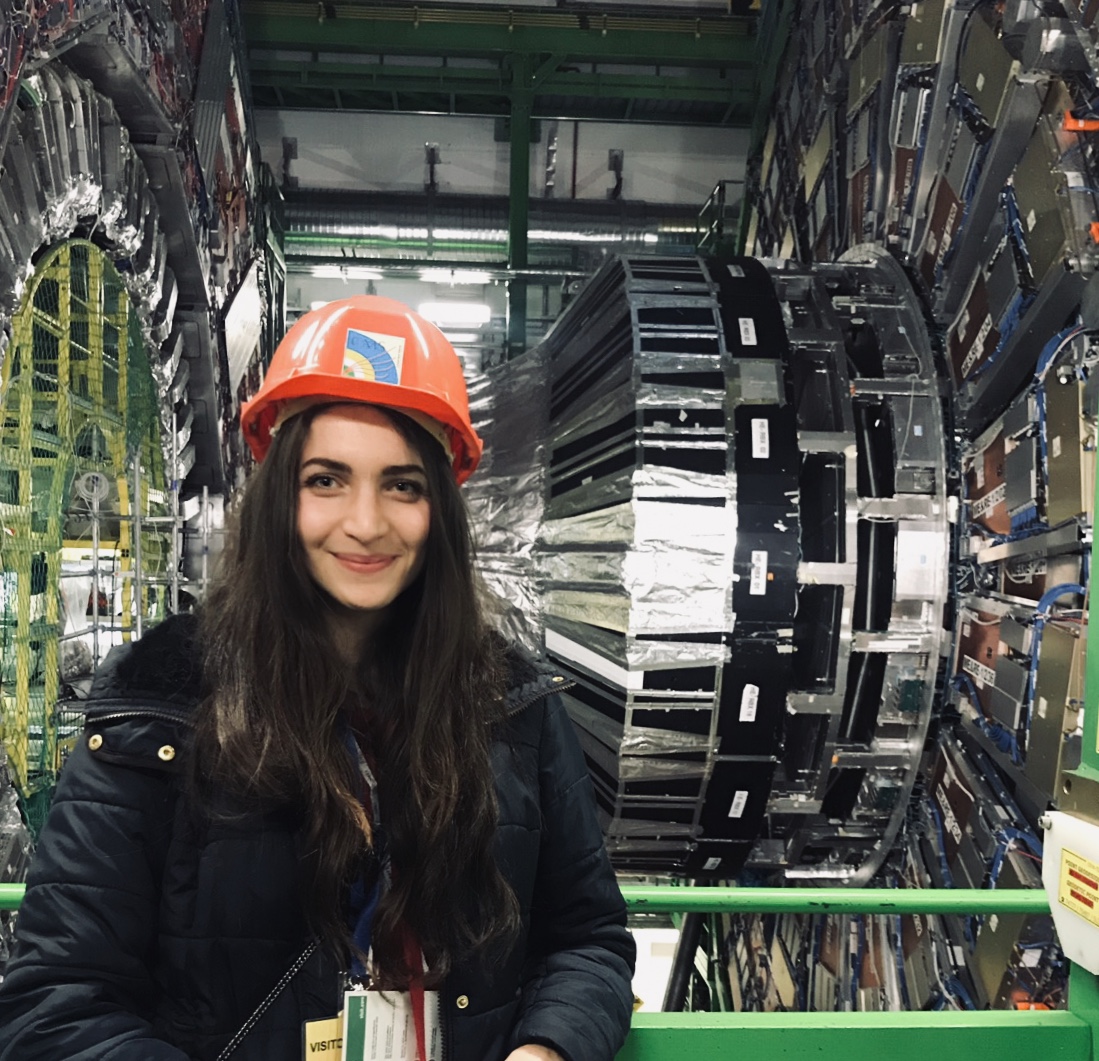

Me: (PhD student, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

Me: (PhD student, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien (IPHC), Strasbourg)

I am Douja Darej, PhD student in the CMS group of Strasbourg, working on a physics analysis searching for supersymmetric long-lived particle decaying into a top quark, and participating in the development of the software used to reconstruct the trajectories of particles in the CMS tracker.

Learning about the infinitely small has always had a huge impact on my perception of this world and my mixed feelings towards it. I started to get interested in particle physics at a very young age. It was a natural and spontaneous path for me to follow afterwards. With everything I learned, from the physics concepts and how they described perfectly what I have always seen as obvious or futile, to the incredible power of mathematics as a universal language, my sensitivity grew and I felt closer to what we call “life". But it is undeniably a path paved with constant questioning and growing unsatisfied curiosity. My relationship to matter, energy, space and time has evolved, and is still finding new ways to expand. The trust we have towards hard sciences is a powerful tool we use to separate between the part where our proximity to nature makes us feel small and weak, and the strength we need in our daily life where our feelings, emotions, environment and events shape our destinies. It is the space where our vulnerability and ignorance is also our strength and our main source of knowledge. On another hand, it gives everything a very special meaning where I don’t feel like I live only to exist, but also to understand the world around me and myself, to wonder if what I know is true, and to dive in my imagination each time there is a blurred spot to find new ways to fill the void by looking for information and create additional links inside my brain until it starts to make sense again.

What still impresses me everyday is how neutral nature is when it comes to how it works. It brings me a kind of peace to witness so many incredible minds and brains working all together on topics that are detached from the big fields that we see all around like politics, economics, fame and glory. It takes a leap of faith to break free from the delusion of what seems to be important, and it gives our perception of the reality a very grounded meaning and a hardly breakable basis to build our personality and opinions on. With particle physics, I never felt closer to the truth, and I never felt closer to myself.

The views expressed in CMS blogs are personal views of the author and do not necessarily represent official views of the CMS collaboration.